What is a convenience sample? When it works, when it fails, and how to use one

Convenience sampling is one of the fastest, most common ways to collect data because it relies on whoever is easiest to reach: your email list, people who walk past a stand at an event, a class of college students, or an online community that already follows your brand.

It's a practical tool for initial research, pilot testing, and quick iterations when you need directional insight, not decision-grade certainty.

At the same time, convenience samples carry real risks. The sample may poorly represent the full target population, creating selection bias that's hard to detect from the data alone. Teams can end up overconfident about findings that don't generalize, even when the sample size looks impressive.

This guide keeps things practical.

You'll get a clear convenience sample definition – including a convenience sample definition in statistics and psychology – real convenience sample examples, the advantages and disadvantages, a set of tactics to reduce bias so you can defend your approach with confidence, and a simple reporting standard you can copy into your methodology.

What is a convenience sample?

A convenience sample is a group of participants selected because they are easy to access, not because they accurately represent the entire population you care about. In other words, convenience sampling relies on availability – sometimes called availability sampling, opportunity sampling, or accidental sampling – rather than random selection.

That one detail changes how you interpret results. With probability sampling, each population member has a known chance of selection, often via a sampling frame and random sampling techniques. With a convenience sampling technique, the chance of inclusion is unknown, uneven, and shaped by access, timing, and willingness to respond.

What this means in practice depends on your context:

- Business surveys – You might survey customers who opened last month's newsletter or users who clicked a feedback widget. That's fast and low cost, but it's not automatically a representative sample of your full customer base or target market.

- Academic research – A campus study using college students is often a convenience sample. The sample units are accessible, but demographic factors and shared context can skew outcomes.

- Quick UX studies – Product teams often use convenience samples for hypothesis generation, usability checks, and refining qualitative and quantitative questions before investing in broader data collection.

Convenience sampling can work well when your goal is learning quickly, testing survey wording, or identifying obvious issues. It becomes risky when you use it to generalize data to the total population without acknowledging that the sample may not match the full target population.

The key is to keep your claims aligned to your sampling method, which leads directly to the most important distinction to understand: the gap between your sample and the population you actually want to study.

Convenience sample vs. the target population

Your target population is the particular population you want your research findings to apply to, such as:

- All employees globally

- All customers in the last 12 months

- All adults in a region.

- All people who walk past and can be persuaded to take a survey

Your sampling frame is the list or channel you can realistically recruit from. In many real projects, that frame is incomplete – there's a sample size gap between the population you want and the contacts you can actually reach.

A convenience sample is, effectively, whoever shows up, which can be fine for early-stage learning, but it increases the chance that your sample doesn't represent the population.

A convenience sample definition in statistics

In statistics, a convenience sample is a non-probability sampling approach. Many statistical guarantees assume probability sampling, where random selection gives every unit a known, non-zero chance of inclusion.

When you move to nonprobability sampling:

- Sampling error is no longer straightforward. In a simple random sample, you can estimate sampling error and calculate confidence intervals tied to that random selection process. With convenience samples, you usually can't estimate sampling error the same way because the selection mechanism is unknown.

- Representativeness is uncertain. Even if you collect a large sample size, biased recruitment can still produce biased estimates derived from the data.

- Generalization is limited. You can still summarize what your sample said. It's harder to justify claims about population parameters for the entire population.

That doesn't mean you can't do useful analysis; it means you should report results in ways that fit the method:

- Descriptive statistics first – Percentages, means, medians, distributions, and segment comparisons within the sample.

- Confidence intervals with caveats – If you report intervals, make it clear they rely on assumptions that may not hold under nonprobability sampling.

- Sensitivity checks – Re-run analysis with reasonable alternative assumptions, or compare results across demographic subsets to see whether conclusions depend on one group.

- Replication across multiple samples – A second convenience sample recruited through a different channel can act as a stability check. If results flip, you've still learned something important.

- Benchmarking where possible – Compare your sample's demographics to known population benchmarks (internal CRM data, HR records, census data, etc.) to see where noncoverage might sit.

It's important to also be aware of the margin of error, rather than treating calculator output as a guarantee of representativeness. More responses do not automatically fix biased sampling.

Once you accept that uncertainty, the real challenge becomes identifying bias you can't directly observe.

Why selection bias is hard to measure

Selection bias can be directional and invisible without a benchmark.

If your convenience sampling relies on an email list, your sample may tilt toward people who open emails. If it relies on an in-product pop-up, it may tilt toward heavy users. If it relies on volunteers, it may tilt toward people with stronger opinions, more time, or higher motivation.

The tricky part is that your dataset can still look clean. You can have a tidy distribution, consistent responses, and enough completes to run analysis. None of that proves the sample matches the target population.

Bias also isn't always obvious from demographics alone. Two people with the same job title might respond differently depending on how they found the survey, whether they trust the sponsor, what they think the survey will be used for, and simply how they're feeling at the time. That's why the best practice is not to assume bias is small, but design and report in a way that makes bias less likely and easier to spot.

This becomes especially visible in psychology, where convenience samples have shaped whole research areas, and where researchers have built a set of safeguards worth borrowing in business research too.

A convenience sample definition in psychology

In psychology, convenience sampling is practical, so it shows up everywhere. Researchers often recruit from:

- Participant pools at universities

- Campus studies with college students

- Online volunteer recruitment, such as social media, forums, and opt-in panels

- Lab studies where the easiest-to-reach participants live nearby and can attend in person

The convenience sample definition in psychology is the same at its core: participants are selected because they are available and willing, not because they represent the full population.

Why it matters is also clear in psychology:

- Demographic skew – College samples often skew younger, more educated, and concentrated in one region or culture.

- Culture effects – Findings from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) samples may not generalize globally, even when the theory sounds universal.

- Motivation and demand characteristics – People may guess what the study is about and adjust behavior, especially in lab settings or when incentives are involved.

- Context effects – Where and how you recruit influences who participates and how they interpret questions.

The upside is that psychology has developed practical habits for living with these limitations. Even if you're running market research instead of lab experiments, those safeguards translate well, and they set up the real-world scenarios where convenience samples are most common.

Common psychology safeguards

Psychology researchers often reduce risk by adding structure around a convenience sample, such as:

- Screening and inclusion criteria so the sample aligns with the research question

- Attention checks to improve data quality

- Preregistration to reduce flexibility in analysis and reporting

- Replication across multiple samples to see whether effects hold

- Transparent limitations that tie claims to the sample used

With that foundation, it's easier to spot convenience samples in everyday survey research, including the places teams forget they're using them.

Convenience samples in the real world

Psychology makes convenience sampling feel academic, but the same pattern shows up in day-to-day data collection. If the recruitment method boils down to whoever is available, you're probably looking at a convenience sample.

Common real-world convenience samples include:

- Employee pulse surveys sent through internal channels

- Customer pop-ups or in-product feedback prompts

- Email list surveys

- Social media polls

- Event intercepts, like the local-mall-clipboard approach)

- Post-support-ticket surveys that only reach people who contacted support

A quick checklist helps:

- Recruitment depends on who happens to see the survey

- No sampling frame covers the full target population

- Participation is opt-in, and you don't know who ignored it

- Timing and channel choices strongly shape who responds

Convenience sampling work tends to be strongest when it's used for iteration, not for sweeping conclusions. That's especially true in business research, where speed is valuable, but decisions still need defensible evidence.

Convenience samples in business research

In business, convenience samples are often the only realistic option for early research. They're low cost, they have fewer rules than probability sampling, and they can quickly surface patterns worth exploring.

The tradeoff is that your claims must stay aligned with the sample. A customer pop-up can tell you how current active users feel today. It cannot automatically tell you how your entire customer base will behave next quarter.

Teams get the most value when they treat convenience samples as a fast learning loop:

- Use convenience sampling for initial research, pilot testing, and improving survey design

- Use stronger sampling techniques – quota sampling, stratified sampling, or probability sampling – when the decision needs generalizable estimates

Now, let's make this concrete with convenience sample example scenarios you can learn from.

5 Convenience sample examples

The easiest way to understand a convenience sample is to see it in action. Here are five examples of convenience sampling across common settings, each with a clear boundary on interpretation.

Employee pulse survey via an internal chat channel

Who you sampled: Employees who actively use the company chat tool and noticed the link during the recruitment window.

What you learned: Directional sentiment, immediate themes, and areas for follow-up in qualitative questions.

What you cannot claim: Company-wide engagement levels for all employees, especially if frontline teams or shift workers have lower access.

In-product feedback widget

Who you sampled: Current users who logged in and chose to respond, often power users.

What you learned: Pain points in the workflow, feature requests, who some power users are, and a quick read on usability.

What you cannot claim: Opinions of churned users, infrequent users, all users, or prospects evaluating alternatives.

Local mall intercept survey

Who you sampled: People physically present at one location, at one time, who agreed to participate.

What you learned: Immediate reactions to messaging or packaging, plus fast A/B checks.

What you cannot claim: Market-wide demand or preferences across regions, demographics, or shopping contexts.

Social media poll

Who you sampled: People who follow your account (or saw a shared post) and were motivated to vote.

What you learned: Lightweight prioritization signals and language that resonates with your existing community.

What you cannot claim: Any estimate of prevalence in the wider target audience, since noncoverage is usually large.

University participant pool for a psychology study

Who you sampled: Students enrolled in a participant pool, often with incentives tied to course credit.

What you learned: Evidence for a mechanism or effect under controlled conditions, useful for hypothesis generation.

What you cannot claim: That the effect holds for all age groups, cultures, or real-world environments.

A mini case study: from convenience to decision-grade

A product team wants to measure willingness to pay for a new add-on. They start with a convenience sample of 60 current customers from a customer advisory list to validate survey wording and identify confusing price anchors.

They learn that one question creates positivity bias because it frames the add-on as "free time back," which pushes respondents toward higher willingness-to-pay answers. They rewrite the question, add a neutral comparison, and test again with a second convenience sample recruited from a different channel.

Once the survey instrument looks stable, they move to a more structured approach: quota sampling across customer size bands, then a stratified random sampling plan within those bands where they have a usable sampling frame. The convenience samples did their job by de-risking the survey, while the more representative sample supported decision-grade estimates.

If you want to include examples like these in your own work, a clean write-up matters as much as the example itself.

A strong write-up for your example

A short methodology template keeps your convenience sample defensible.

- Recruitment source: Where participants came from – email list, in-product prompt, event intercept, or online community

- Timeframe: When data collection happened, including the recruitment window

- Inclusion criteria: Any screeners or required characteristics

- Sample size: Number invited (if known), number started, andnumber completed

- Key demographics collected: The variables you measured to understand skew

- Data cleaning: Exclusions, duplicates, attention checks, and bot filtering

- Limitation statement: Exactly what the sample supports and what it does not support

That structure makes it easier to spot when convenience sampling is a smart choice. It also sets up the next question most teams ask: why use convenience sampling at all if the limitations are so real?

What are the advantages of a convenience sample?

The advantages of convenience sampling are mostly practical. When teams use convenience sampling well, it's because the method matches the goal.

Common advantages include:

- Speed – You can collect data quickly, which is valuable for iteration and time-sensitive research questions

- Low cost – No expensive recruitment, no complex sampling frame requirements

- Simple logistics – Fewer operational steps than probability sampling or systematic sampling

- Strong fit for pilot testing – Great for validating survey flow, wording, and completion time before broader rollout

- Helpful for hypothesis generation – Early signals can guide further research and help refine what you test next

- Works for quick qualitative and quantitative questions – You can gather data fast, then decide whether a bigger study is worth it

Convenience samples are also useful when you're studying a particular population that is inherently hard to reach, and your best option is an accessible subset. In those cases, the goal is not perfect representativeness, but well-documented recruitment and transparent limitations.

Of course, those benefits come with tradeoffs. To use convenience sampling responsibly, you need to be specific about the disadvantages, including the newer risks that show up in online surveys.

What are the disadvantages of a convenience sample?

The biggest disadvantage is simple: a convenience sample may not represent the target population, which weakens your ability to generalize results.

More specifically, disadvantages include:

- Selection bias – People self-select based on motivation, availability, or interest, and that can shift your results in a consistent direction

- Noncoverage – Parts of the population are missing because they never had a chance to be included; it was the wrong channel, the wrong timing, or due to limited access

- Volunteer bias – Respondents who opt in may have stronger opinions, more extreme experiences, or more time than typical population members

- Skewed demographics – Age, location, income, education, and role differences can distort conclusions

- Overconfident conclusions – Teams treat sample estimates as population parameters, especially when charts look clean

- Low external validity – Even if findings are internally consistent, they may not hold outside your sample and context

Modern survey pitfalls add another layer, especially when you use open links:

- Duplicate submissions from the same person across devices or sessions

- Professional survey-takers who speed through for incentives

- Context effects from recruitment source – an in-product survey produces different answers than a neutral email invite

- Bots and automated responses, especially for public surveys

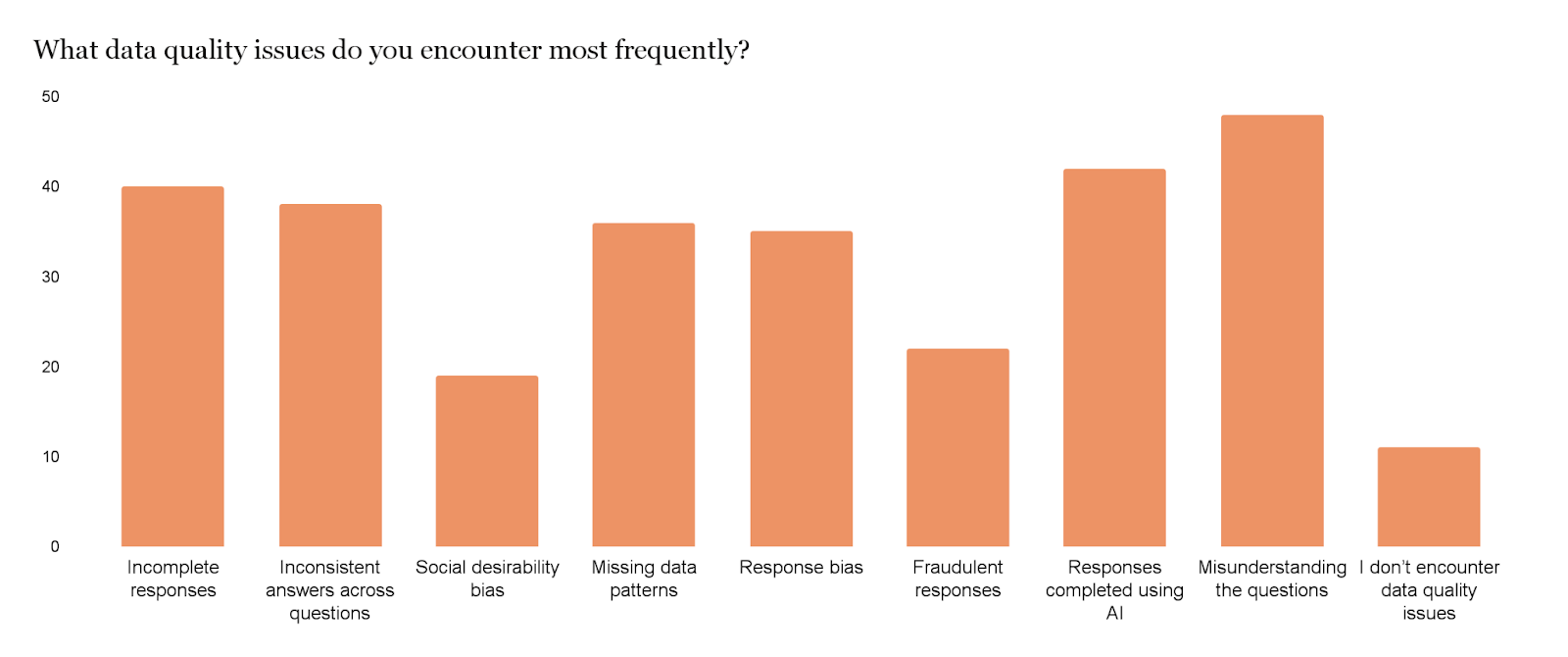

Regarding bots, in our recent survey, it was clear that AI responses are making it harder for researchers to get accurate data, with "responses completed using AI" the second most common quality issue they faced.

Nonprobability sampling can also tempt teams to apply probability-style language too confidently, which may be fast and inexpensive, but drawing conclusions about the population typically requires assuming the sample is representative – which is often a risky assumption.

Here's a full comparison of the advantages and disadvantages:

The good news is that you can reduce bias without turning your project into a full probability sampling operation. Start with practical tactics, then add structure and cleaning based on what your study can support.

How to reduce bias in convenience sampling

Reducing bias starts before you collect data. The goal isn't to pretend a convenience sample is representative, but to make it less skewed, easier to interpret, and easier to replicate.

Actionable tactics that work in most survey research:

- Define the target population in one sentence, then list what your convenience sample is likely to miss

- Use screeners to filter respondents so the sample aligns with the research question

- Recruit across multiple channels to reduce single-source skew

- Set quotas where possible so one demographic subset doesn't dominate

- Track and report key demographics so readers understand who responded

- Document exclusions and drop-off so the final sample is transparent

- Re-run the study with a second convenience sample to check whether the results are stable

A "good, better, best" framework makes it easier to level up:

- Good – One channel, clear limitations, and descriptive reporting

- Better – Multiple channels, screeners, basic quotas, and demographic tracking

- Best – Multiple samples, structured quotas, benchmark comparisons, and a follow-up study using a more representative sampling method when decisions require it

The next step is adding a lightweight structure so your convenience sample is at least consistent and repeatable.

Add a lightweight structure

Lightweight structure is often the difference between "quick and messy" and "quick and usable."

- Quotas – If you can't do random selection, quota sampling can still prevent extreme imbalance across key segments

- Time-box recruitment – Keep windows consistent and avoid leaving surveys open indefinitely

- Consistent inclusion criteria – Use the same screeners and definitions across waves so results are comparable

- Track your sampling frame – Even if it's imperfect, document the channels and lists used so others can interpret noncoverage

If your survey tool supports response limits and quotas, you can operationalize this without manual monitoring. Checkbox includes response limits and quota controls that help manage recruitment windows and cap responses as they come in.

Once a structure is in place, data cleaning protects you from the most common online survey risks.

Clean the data

Data cleaning keeps convenience samples from getting quietly polluted. Do the following:

- Attention checks – Filter low-effort responses and reduce noise

- Dedupe where possible – Remove repeat submissions and suspicious patterns

- Bot protection – Add a CAPTCHA when you're using open links

- Suspicious-pattern review – Look for unreal completion times, straight-lining, or repeated identical strings in open text

Checkbox supports CAPTCHA options designed to prevent spam and automated submissions, which can be especially useful when you're collecting data through public links.

After bias reduction and cleaning, your last line of defense is honest reporting. A well-written methodology keeps you credible and helps others understand what your findings can and cannot support.

How to report a convenience sample in your methodology

A simple reporting standard makes convenience samples easier to trust:

- Who you recruited – Population definition and inclusion criteria

- Where you recruited – Channels and sampling frame details

- When you recruited – Dates and recruitment window

- How you recruited – Invitation method, incentive (if any), and whether participation was opt-in

- Sample size – Invited (if known), started, completed, and analyzed

- Key characteristics – Demographics and any relevant behavioral variables

- Data quality steps – Exclusions, attention checks, bot prevention, and deduping

- Limitation statement – Tie limitations directly to claims and external validity

If you want a tighter link between claims and evidence, it helps to compare convenience sampling to other sampling methods so you can choose the lightest option that still supports your decision.

Convenience sampling vs. other sampling methods

Convenience sampling is one of several nonprobability sampling strategies. The right choice depends on whether you need speed, specificity, or defensible generalization.

Other nonprobability options include:

- Purposive sampling – You intentionally recruit people with certain characteristics, which is useful for qualitative depth

- Quota sampling – You set target counts for subgroups to reduce imbalance

- Snowball sampling – Participants recruit other participants, often used for hard-to-reach groups

- Volunteer sampling – Similar to convenience, but explicitly based on self-selection through a public call

Probability sampling options are stronger for generalization. Here are a few examples:

- Simple random sampling – Each unit has an equal chance through random selection

- Stratified sampling – You divide the population into strata and sample within each stratum

- Cluster sampling – You randomly select clusters, such as schools or regions, then sample within them

- Systematic sampling – You select every k-th unit from an ordered list after a random start

If the goal is exploratory learning or pilot testing, convenience sampling is often the most efficient. If the goal is to estimate population parameters or make policy-level decisions, probability sampling or at least a structured approach like stratified sampling is usually the better fit.

Once you decide a convenience sample is appropriate, the next step is running it in a way that keeps the project fast without letting quality slide.

Using Checkbox to run a convenience sample survey

Convenience samples move quickly, so your survey workflow needs to keep up. The goal is to launch fast, control access where needed, and keep data organized so you can analyze results with clear limitations and next steps.

A practical flow with Checkbox looks like this:

- Build the survey

Use a no-code survey builder to draft the instrument, then keep the first version simple so you can pilot quickly.

- Add screeners and branching

Use screeners early in the survey to focus on the target audience you can realistically reach. Then use conditions and branching so respondents only see relevant questions, which keeps your survey shorter and improves completion rates.

- Control access based on your risk level

For the fastest recruitment, a public link may be enough. If you need stronger control, set the survey to email invitation only so only invited contacts can respond.

- Add a lightweight structure

If you're trying to balance demographic subsets, set response limits and quotas so one segment doesn't flood the dataset early.

- Protect data quality

If you're sharing an open link, add CAPTCHA to reduce bot submissions.

- Monitor responses and summarize responsibly

Use reporting and analysis to summarize descriptive results, document exclusions, and write a limitation statement that matches what the sample supports.

Checkbox also supports flexible hosting approaches, including cloud and on-premises options, which can matter when your organization has specific security or compliance constraints.

With the right workflow, convenience samples stay what they should be: fast, structured learning that feeds into better decisions, better surveys, and clearer next research steps.

Final thoughts

Convenience samples are everywhere because they solve a real problem: you often need to collect data now, not in six months after building a perfect sampling frame.

They can be a smart sampling method for speed, pilot testing, and hypothesis generation. It becomes unreliable when teams overgeneralize findings to the full target population, treat sample estimates as population parameters, or ignore selection bias and noncoverage.

If you keep your claims matched to your sampling technique, add a lightweight structure, clean the data, and report transparently, convenience sampling can still produce meaningful insight and guide further research.

If you're ready to run a convenience sample survey with more control and clearer reporting, Checkbox helps you build surveys quickly, add screeners and branching, manage access, and move from data collection to decisions. Explore Checkbox's survey solutions and request a demo when you want to level up from quick learning to research you can stand behind.

Contact us

Fill out this form and our team will respond to connect.

If you are a current Checkbox customer in need of support, please email us at support@checkbox.com for assistance.