What is a double-barreled question? A quick definition with examples and fixes

One tiny wording slip can turn a clean survey question into two questions wearing a trench coat. You ask for a single answer, but you’re accidentally measuring two different things. The result is confused respondents, unclear insights, wasted time, and decisions built on inaccurate data.

The frustrating part is that double-barreled questions are easy to write. Double-barreled questions are one of the most common survey question errors researchers make. They’re easy to write without realizing, but thankfully, just as easy to fix.

This guide walks you through what double-barreled questions are, why they distort your survey results, and how to rewrite them to get cleaner, more actionable insights.

What is a double-barreled question?

A double-barreled question asks about two separate topics in the same question, but only provides space or allows for one answer. The respondent can't indicate how they feel about each issue individually, so you're left guessing which part of the question they actually addressed.

Here's a classic double-barreled question example: "How satisfied are you with our product quality and customer service?"

If someone gives this a rating of 3 out of 5, you have no way of knowing whether they found the product or the service lacking, or both just found it middle of the road. The single answer hides two potentially opposite opinions.

Here’s another example that might appear in an employee survey: "Do you feel supported and challenged in your role?"

An employee might feel deeply supported by their manager but uninspired by their tasks. When forced to give one response, the data becomes meaningless.

So, why "double-barreled?" Here's a quick double-barreled question definition: It comes from the idea of firing two shots at once – you can't tell which one hit the target.

Some researchers also call this a compound question or double direct question, but the core problem remains the same: one question asks about two different issues, making it impossible for survey respondents to give a clear answer.

Why double-barreled questions distort results

Understanding the definition is one thing. Seeing the practical damage is another. Once a question asks about two different issues, the response becomes ambiguous by design. Even if your reporting looks tidy, the meaning underneath can be shaky.

When respondents encounter a double-barreled survey question, they typically react in one of three ways:

- Some choose to answer only the part that feels most important to them, ignoring the other half entirely

- Others mentally average their feelings and select a middle option that doesn't reflect their true opinion on either topic

- A third group simply skips the question altogether, frustrated by the lack of appropriate response options

Each of these reactions corrupts your survey data in a different way. Consider a scenario where you're measuring satisfaction with a new software tool.

You ask: "How easy and useful do you find this software?" Your results show an average score of 3.5 out of 5. Leadership interprets this as "moderately positive" and moves on.

But here's what actually happened:

- Half of your respondents found the software incredibly useful but confusing to navigate.

- The other half found it intuitive but ultimately pointless for their workflow.

- Both groups rated their experience as middling because they couldn't separate the two attributes.

Your "moderately positive" result masks two urgent problems that require completely different solutions.

Double-barreled questions also increase survey drop-off rates. When respondents feel they can't answer honestly, they become disengaged. They rush through remaining questions or abandon the survey entirely. The harder you make it for people to respond accurately, the less reliable your entire dataset becomes.

With the damage now clear, let's look at how these questions show up across different survey types, and how to fix the questions in each.

7 double-barreled question examples

Double-barreled questions can accidentally appear in nearly any survey format. Below are seven examples spanning employee feedback, customer experience, product research, training evaluation, and support surveys.

You'll find the problematic original, an explanation of why it fails, and a rewritten version that captures both concepts separately.

1. Employee engagement survey

Original: "Do you feel recognized and supported by your manager?"

Recognition and support are distinct managerial behaviors. An employee might receive regular praise but lack the resources or guidance they need to succeed. Combining these topics hides which area requires attention.

Rewrites:

- "How often does your manager recognize your contributions?"

- "How supported do you feel by your manager in achieving your goals?"

2. Customer satisfaction survey

Original: "How satisfied are you with our pricing and product quality?"

A customer might love your product but find it overpriced – or consider it a bargain despite quality concerns. This question bundles two separate purchase drivers into one response.

Rewrites:

- "How satisfied are you with the quality of our product?"

- "How satisfied are you with our pricing?"

3. Product feedback survey

Original: "Is our app fast and easy to use?"

Speed and usability are related but not identical. An app might load instantly but have a confusing interface, or it might be intuitive but sluggish. Respondents can't accurately rate both with a single answer.

Rewrites:

- "How would you rate the speed of our app?"

- "How easy is our app to navigate?"

4. Training evaluation survey

Original: "Was the training session informative and engaging?"

Information density and engagement level measure different outcomes. A session packed with valuable content might still put participants to sleep, while an entertaining session might lack substance. Separating these helps you improve future training design.

Rewrites:

- "How informative was the training session?"

- "How engaging was the training session?"

5. Support experience survey

Original: "Was our support team helpful and quick to respond?"

Helpfulness and response time are both critical to support quality, but they don't always align. A support agent might reply within minutes but fail to resolve the issue, or they might take a day but provide a thorough solution.

Rewrites:

- "How helpful was our support team in resolving your issue?"

- "How satisfied are you with the response time of our support team?"

6. Work environment survey

Original: "Do you have the tools and training you need to do your job effectively?"

An employee might have excellent software and equipment but lack proper onboarding or skills development. Alternatively, they might be well-trained but working with outdated technology. Each scenario requires a different organizational response.

Rewrites:

- "Do you have the tools you need to perform your job effectively?"

- "Do you have the training you need to perform your job effectively?"

7. Brand perception survey

Original: "Do you find our brand trustworthy and innovative?"

Trustworthiness and innovation are distinct brand attributes. A legacy company might be highly trusted but seen as stagnant. A startup might be viewed as cutting-edge but unproven. Measuring these separately reveals where your brand positioning needs work.

Rewrites:

- "How trustworthy do you consider our brand?"

- "How innovative do you consider our brand?"

Notice how many double-barreled questions contain "and" or "or" joining two concepts. This pattern appears in rating scales that blend multiple attributes, agree-disagree statements that bundle unrelated ideas, and questions that combine past experience with future intent. The fix is always the same: match each question to one metric, one concept, and one clear answer.

How to fix double-barreled questions

Identifying double-barreled questions is straightforward once you know what to look for. Fixing them follows a simple, repeatable process.

Start by reading each question aloud and asking: "Does this question address more than one topic?"

If you find yourself using "and" or "or" to connect two ideas, you've likely written a compound question. However, don't rely on conjunctions alone, as some unclear questions – though maybe not "double-barreled" – hide their dual nature through implication rather than explicit phrasing.

For example, asking a new employee "How satisfied are you with your onboarding experience?" may seem straightforward, but an onboarding experience could factor in several parts of the experience, from the materials used to the quality of the training. In this instance, either break the question down by factor or add another open-ended question to get more details from the respondent.

After you've read each question aloud, identify the separate concepts within the question. Write each one down as its own statement. For the question "How satisfied are you with our delivery speed and packaging quality?" you'd list: delivery speed, packaging quality. These become the foundations of your rewritten questions.

Next, decide whether you actually need both pieces of information. Sometimes survey creators accidentally include redundant questions or topics that don't align with their research goals. If a concept doesn't connect to a decision you'll make based on the data, consider removing it entirely rather than splitting the question.

For concepts you do need, write separate questions using parallel structure. If one question asks "How satisfied are you with X?" the companion should ask "How satisfied are you with Y?" Consistency in phrasing helps respondents understand what you're asking and makes your data easier to compare.

Finally, ensure each question has appropriate answer options. A question about frequency needs a different rating scale than a question about satisfaction. Match your response options to what you're actually measuring.

This process takes only a few minutes per question but dramatically improves the quality of your survey data. Speaking of quality, a final review before launch can catch any remaining issues.

A quick quality check before you launch

Before distributing your survey, run through this checklist to catch double-barreled questions and other common pitfalls:

- One concept per question. Each question should measure exactly one thing. If you can split a question into two without losing meaning, or even further clarifying it, it needs splitting.

- One timeframe. Avoid questions like "How has your experience changed over the past month and year?" Specify a single period.

- One subject. Don't ask about multiple people, products, experiences, or departments in the same question.

- One action. Questions should focus on a single behavior or outcome, not a sequence of activities.

- One scale. Ensure your response options match what you're measuring. Don't ask a satisfaction question with frequency-based answers.

- No hidden assumptions. Make sure your question doesn't assume the respondent has a particular experience, opinion, or background.

- Neutral wording. Avoid language that pushes respondents toward a particular response.

After completing this checklist, pilot test your survey with a small group. Ask them to explain their interpretation of each question. If multiple testers understand the same question differently, you have an ambiguity problem. If testers struggle to answer because the question covers too much ground, you likely have a double-barreled question that slipped through.

Pilot testing adds time to your survey development process, but it prevents far greater time loss from analyzing confusing or unusable data. Of course, double-barreled questions aren't the only survey design issue worth avoiding.

Other survey question mistakes to avoid

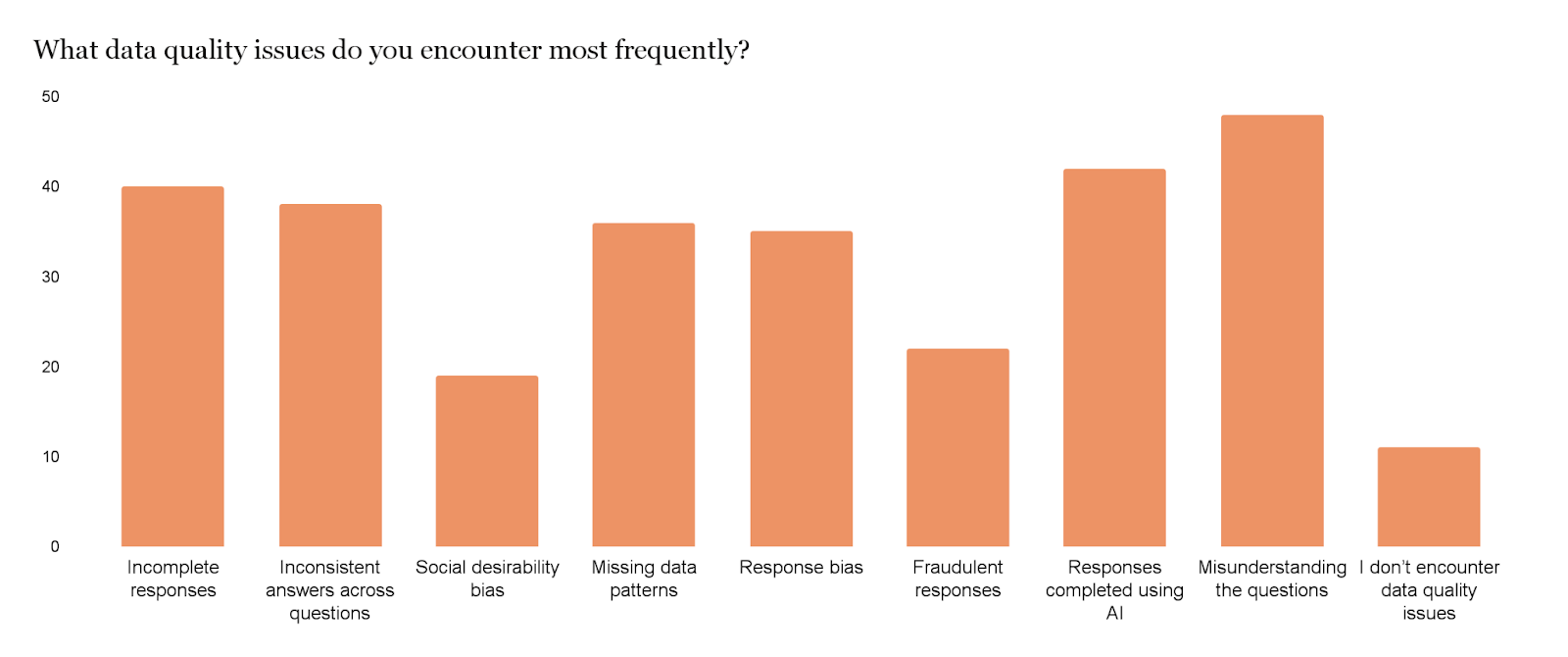

Double-barreled questions are just one type of survey question error that leads to respondents skipping or misunderstanding a question. In fact, in our recent survey of market researchers and insights professionals, we found that “Misunderstanding the question” was the most common data quality issue survey creators faced.

A thorough quality review should also check for these related problems:

Leading questions push respondents toward a specific answer through biased language. For example: "How much do you love our new feature?" assumes the respondent loves it at all.

Ambiguous questions use vague terms that different respondents interpret differently. For example: "Do you exercise regularly?" means daily to one person and monthly to another.

Double negative questions confuse respondents with twisted phrasing. For example: "Do you disagree that the policy should not be changed?" requires mental gymnastics to parse.

Assumptive questions presume facts that may not apply to all respondents. For example: "How often do you use our mobile app?" assumes the respondent uses it at all.

Loaded questions embed controversial premises into seemingly neutral phrasing. For example: "Do you support the wasteful spending on this project?" frames the spending as wasteful before the respondent can evaluate it.

Adding these checks to your survey QA process helps ensure you collect accurate, actionable data. Once your questions are clean, you need the right tools to build and distribute your survey effectively.

Create clearer surveys with Checkbox

Good survey design deserves software that supports it. Checkbox's no-code survey builder makes it simple to structure clear, focused questions without developer involvement. When you realize a question needs splitting, you can duplicate and modify it in seconds rather than rebuilding from scratch.

With Checkbox, you can:

- Build and edit without friction – Use a no-code survey maker to create separate questions quickly, without rewriting layouts every time.

- Use skip logic so respondents only see what applies – Conditions and branching help you avoid assumptive questions and reduce drop-off. If someone rates product quality as "poor," you can immediately ask a follow-up about specific issues – keeping each question focused on one topic while still gathering the context you need.

- Standardize across teams and other brands – Templates and reusable components make it easier to keep question wording consistent, even when multiple departments ship surveys. When you build a set of well-crafted employee engagement questions, you can save them for future use rather than reinventing (and potentially making mistakes) each time.

- Support research where data control matters – The platform also supports on-premise deployment for teams with strict data sovereignty requirements, white-label options for consistent branding, and analytics to help you turn clean data into clear insights.

Final thoughts

Every survey question should measure one thing. That's the core principle behind avoiding double-barreled questions – and it's the foundation of survey data you can actually trust.

Before launching your next survey, scan every question for compound concepts. Split or remove any that ask respondents to evaluate multiple topics at once. When you need context behind a rating, add a separate open-ended follow-up rather than cramming two questions into one.

Clear questions lead to clear answers. Clear answers lead to decisions you can stand behind.

Ready to build surveys that collect data worth acting on? Try Checkbox and see how no-code editing, logic-driven flows, and flexible deployment options make better survey design achievable for any research team.

Double-barreled question FAQs

A common double-barreled question example is: "Do you agree that our website is attractive and easy to navigate?"

This question combines two distinct attributes – visual appeal and usability. A respondent might find the website beautiful but confusing, or plain but intuitive.

With only one answer allowed, neither the respondent nor the researcher can separate these two evaluations. The fix is to ask about attractiveness and ease of navigation in separate questions.

A double-barreled question in research is a survey or interview question that asks about two or more topics simultaneously but only allows one response.

This lack of clarity makes it impossible to determine which topic the respondent is addressing, leading to ambiguous data that researchers cannot interpret accurately.

It's considered an informal fallacy in questionnaire design because it violates the principle that each question should have one clear meaning.

Identify the separate concepts within the question, then write a distinct question for each one.

For example, "How satisfied are you with our service speed and quality?" becomes two questions: "How satisfied are you with our service speed?" and "How satisfied are you with our service quality?"

Ensure each question uses appropriate response options and measures only one attribute.

Contact us

Fill out this form and our team will respond to connect.

If you are a current Checkbox customer in need of support, please email us at support@checkbox.com for assistance.